Yuyao Tong, Chao Yang, Pengjin Wang, Gaowei Chen

yyttong@hku.hk, chaoyang@connect.hku.hk, wangpj@connect.hku.hk, gwchen@hku.hk

The University of Hong Kong

Abstract: This study aimed to investigate students’ understanding and engagement of productive discourse supported by a video-based analytics-supported approach, using the Classroom Discourse Analyzer tool to help students engage in collective reflections and understand classroom talk. A total of 33 9th grade students in Hong Kong participated and inquired into the topic of Art. A key design involved students that were provided with analytics information on classroom discourse, followed by their reflections. Quantitative analysis indicated a significant change in students’ understanding of discourse towards a knowledge building perspective. Qualitative analysis showed key themes of how students engaged in inquiry-oriented classroom discourse for developing their discourse understanding. Implications of using analytics-supported reflection to promote discourse understanding were discussed. By identifying the key factors from the perspective of students’ epistemic discourse understanding, we proposed a future discourse understanding model for knowledge building.

Keywords: discourse understanding, knowledge building, analytics-supported reflection, inquiry learning

1. Introduction

Many studies have examined productive classroom discourse (Howe & Abedin, 2013; Mercer et al., 2019). However, few have investigated how students engage in classroom talk focusing on agency and inquiry-based progressive discourse. Further, it remains unclear how students’ epistemic understanding of the nature of discourse could be developed towards a knowledge building perspective. Increasing attention has been paid to the study of fostering students’ epistemic beliefs about the nature of science, and examining their understanding of epistemic criteria for good scientific models (Pluta et al., 2011; Sandoval, 2005). Overall, there lacks a systematic investigation on how to promote students’ discourse understanding in knowledge building classrooms. This study aims to examine students’ understanding and engagement of productive discourse in a knowledge building environment, that focuses on progressive discourse and community advances, supported by student reflection on information provided by visual learning analytics for enhancing classroom discourse.

2. Theoretical Perspectives

Productive classroom discourse, in which teachers and students contribute and build-on ideas, coordinate and reflect on the process of inquiry, is associated with student learning (Howe et al., 2019). With the changing of educational goals from knowledge acquisition and assimilation to knowledge creation (Paavola et al., 2004), students should be responsible for taking agency to engage in productive discourse and creative work for knowledge innovation. However, helping students engage in productive discourse for developing creative knowledge work is challenging. Initiate-response-evaluation (IRE; Mehan, 1979; Mehan & Cazden, 2015), as a traditional classroom discourse pattern, still plays a dominant role in classroom teaching and learning. In contrast to the IRE pattern, the development of dialogic approaches with teachers scaffolding productive classroom discourse to support student learning has been a recurring research theme.

As a major educational model, knowledge building aims to cultivate students to take collective responsibility to advance community knowledge through progressive discourse - “discourse that gets somewhere, advances on a problem, produces a conceptual artifact” (Bereiter & Scardamalia, 2003, p. 60; Scardamalia & Bereiter, 2014). To guide knowledge building practice, Scardamalia (2002) proposed twelve knowledge building principles (e.g., epistemic agency, improvable ideas, collective responsibility and community knowledge). Substantial evidence indicated the role of knowledge building in students’ conceptual understanding, metacognitive thinking, and epistemic beliefs (Chen & Hong, 2016). However, how students could engage in knowledge building classroom discourse needs further investigation. A growing body of research has demonstrated that the epistemic understanding of the nature of science and its role on students’ learning achievement is important (Greene et al., 2016), but few studies have examined how students’ epistemic understanding of the nature of discourse could be scaffolded.

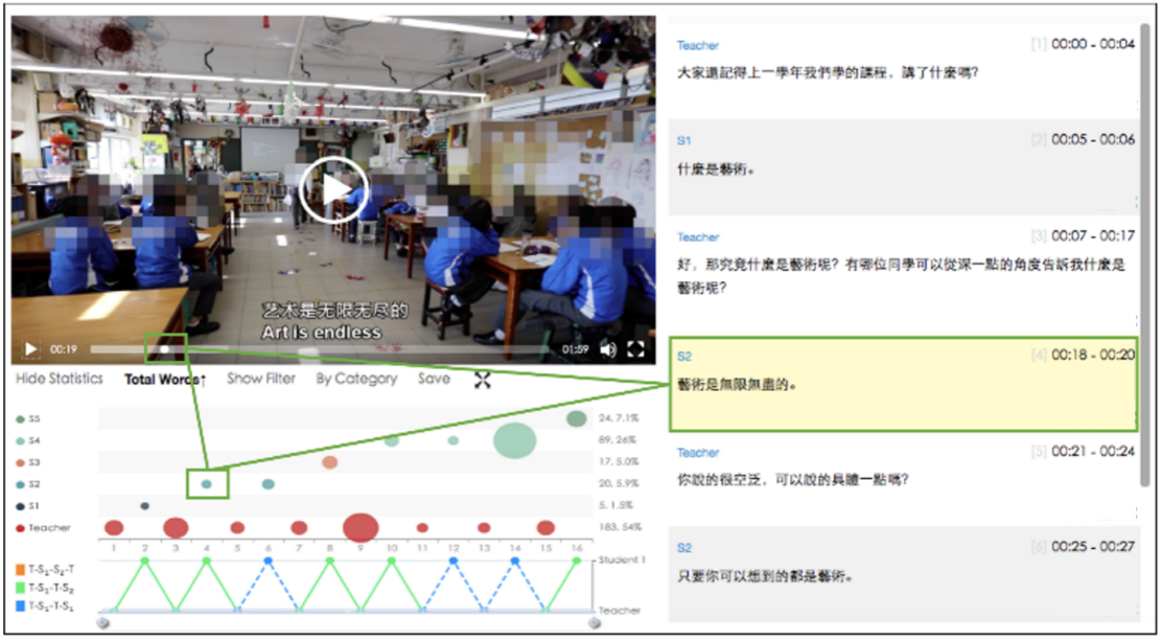

Video-based approach is widely adopted in teacher professional development (Borko et al., 2008; Major & Watson, 2018). Building on research using the video-based analytics-supported approach in helping teachers to facilitate productive discourse in the classroom (Chen et al., 2020, 2022), we extended the approach to help students engage in productive discourse. Current research on classroom talk focuses on teachers’ understanding and strategies (Seidel et al., 2011), and we examined student agency and epistemic understanding of discourse from a knowledge building perspective. Classroom Discourse Analyzer (CDA) (Chen et al., 2015, 2020), a video-based discourse analytic tool, was employed to help teachers and students engage in analytics-supported reflections on their classroom discourse and practice by visualizing classroom discussions. Figure 1 shows a CDA interface that visualizes classroom discourse moves with related videos and discourse transcripts. Specifically, this study designed and implemented an analytics-supported knowledge building environment that focused on collective reflection on classroom discourse. Two research questions were addressed: (1) What are the roles of the video-based analytics-supported approach on students’ epistemic understanding of discourse and domain knowledge? (2) In what ways do students engage in collective inquiry and reflection supported by the video-based analytics-supported approach in developing epistemic understanding of discourse?

Figure 1. An example of the Classroom Discourse Analyzer interface (Note: top left - classroom video; bottom left - frequency of teacher-student talk or talk move coding and teacher-student discourse patterns (Bubble size represents the number of words in a turn); right side - classroom discourse transcripts).

3. Methods and Design

3.1 Research context

Thirty-three 9th grade students studying visual arts, with a teacher of over 15 years’ experience of knowledge building pedagogy participated in this study. The teacher and researchers worked as co-investigators. To develop students’ understanding and engagement of productive discourse, a video-based analytics-supported approach was used to scaffold students' collective reflection.

3.2 Pedagogical design

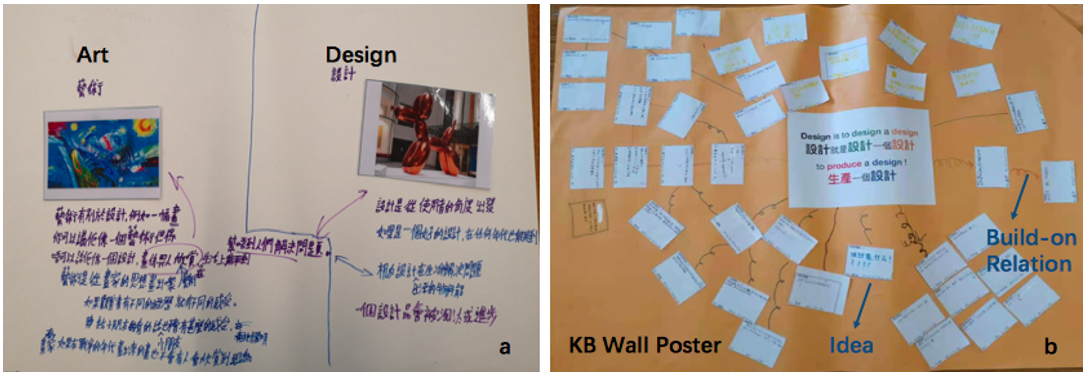

Cultivating a collaborative knowledge building classroom culture (Phase 1). Students were assigned into groups, and they were asked to construct concept maps, inquiring into relations of art and design (see Figure 2a). Each group presented their ideas, with other groups commenting and asking questions using productive discourse, facilitated by the teacher. Through ever deepening dialogues on the understanding of art, each group produced a Knowledge Building Wall (KB Wall) poster (see Figure 2b) to make their ideas public for inquiry. The teacher continued to engage students in productive and progressive knowledge building talk and encouraged students to use prompts to ask other questions (e.g., What is puzzling to you? What do you think before and now? What is another question you can ask? What do you think by putting our ideas together?).

Figure 2. Examples of a group concept map and knowledge building wall poster.

Continuing inquiry and engaging in collective reflection by video-based analytics-supported approach (Phase 2). The video-based learning analytics tool was introduced to students to help them reflect on the classroom discourse. Students collectively reflected on different patterns of classroom discourse using visualization results generated by CDA. Frequencies of teacher-student participation and coding of classroom discourse moves were provided to students on prompt sheets. The teacher had meta-talk discussions with students on their discourse.

Deepening inquiry with written group portfolio reflection notes (Phase 3). Each group was invited to generate a portfolio reflection note to help them reflect on the progress of classroom discourse and knowledge building efforts. Students referred to their KB Wall poster and selected three to six notes to explain their understanding of art and design. The writing of portfolio reflection notes can help students synthesize ideas and identify gaps for further inquiry (van Aalst & Chan, 2007).

3.3 Data sources and analysis

Multiple data sources were collected, including (1) Pre- and post-test of students’ epistemic understanding of discourse, using an open-ended written questionnaire (Tong et al., 2018). The questionnaire was assigned to students before and after the program. A coding framework differentiating knowledge-sharing, knowledge-construction, and knowledge-creation (van Aalst, 2009) was used to code their responses; (2) Pre- and post-test on domain knowledge using an open-ended written test to collect students’ understanding about art and design; a coding scheme adapted from school assessment guidelines was used; (3) Classroom observations of students’ collective inquiry activities, such as group work, classroom discussions, and reflective sessions on the nature of discourse, were conducted; and (4) Artifacts of students’ work, including concept maps, KB Wall posters, and prompt sheets were collected to illustrate how students develop their understanding of discourse.

4. Results

4.1 Changes in epistemic understanding of discourse and domain knowledge

The first research question examined students’ epistemic understanding of discourse from a knowledge building perspective (Table 1). Paired sample t-test indicated a significant difference in students’ pre- and post-test epistemic understanding of discourse, t(32) = - 4.713, p < .001. A significant difference was also obtained in students’ pre- and post-test domain knowledge, t(32) = - 3.076, p < .01. Different examples are included to illuminate patterns as follows.

Table 1. Coding scheme and examples of students’ responses on discourse understanding.

|

Level |

Description |

Examples |

|

0 |

Missing or irrelevant responses. |

“I don’t know” |

|

1 |

Regarding productive discourse as the sharing and accumulation of ideas. |

“A good discourse refers to communicating with each other…everyone expressing ideas together…” |

|

2 |

Regarding productive discourse as a means to solve problems by providing explanations and evidence. |

“A good discourse is to solve problems and construct understanding. We need to provide explanations and examples to support our ideas.” |

|

3 |

Regarding productive discourse as advancing community knowledge by sustained inquiry and reflection. |

“…a good discourse is not merely achieving individual understanding…we need to make contributions to advance our classroom community knowledge…” |

4.1.1 From regarding productive discourse as obtaining an agreement to improving ideas

As Table 2 shows, students’ post-test responses on the understanding of discourse moved more towards a knowledge building perspective that emphasized improvable ideas. Initially, in the pre-test, for example, S108 thought the purpose of classroom discourse was to obtain answers and finish tasks. However, after experiencing the program, S108 now viewed the purpose of discourse as challenging others’ ideas for continuous improvement. She also mentioned using additional sources to improve discussion and reflect changing understanding.

Table 2. Students’ responses to discourse understanding.

|

|

Pre-test |

Post-test |

|

S108 |

“A good discourse refers to communicating with each other…everyone expressing ideas together…the goal of the discussion is to acquire an answer and finish the task assigned by the teacher…” |

“…Besides expressing ideas, we also need to comment and challenge others’ ideas…we can search for relevant information from the Internet to help us deepen our understanding…the goal of the discussion is to continue to improve our initial ideas…” |

4.1.2 From regarding productive discourse as exchanging of ideas to developing collective knowledge

Students’ responses changed from the individual level to the community level. As Table 3 shows, S123 initially thought that the purpose of a discussion was to enrich an individual’s understanding. Later, S123 emphasized the importance of reflection and synthesis for collective knowledge advancement and noted that “…not merely for achieving individual understanding… need to make contributions to advance our class community knowledge…”. This indicates that S123’s understanding of discourse developed towards a knowledge building perspective that emphasized community knowledge advancement.

Table 3. Students’ responses to discourse understanding.

|

|

Pre-test |

Post-test |

|

S123 |

“A good discourse should have a harmonious environment and reach a common understanding…the goal of the discussion is to know others’ ideas and enrich my understanding…” |

“…I initially thought that we need to enrich my understanding through discussion. Now I think that it is still important to deepen my understanding, but a good discourse is not merely achieving individual understanding; more importantly, we need to make contributions to advance our class community knowledge…” |

4.1.3 From regarding productive discourse as mere discussion to synthesizing ideas with reflection

As Table 4 shows, S089 initially thought that a good discourse needed to have a clear focus (e.g., “…should have a common goal…”). In the post-test, S089 started to emphasize the importance of synthesizing key ideas. He referred to his experience reflecting on the classroom discourse videos, saying “…we can synthesize useful ideas from the discussions…”. This example shows that students began to develop an awareness that reflection and synthesizing are two key components in developing knowledge building discourse.

Table 4. Students’ responses to discourse understanding.

|

|

Pre-test |

Post-test |

|

S089 |

“A good discourse should have a common goal and classmates should focus on the discussion topic instead of talking about irrelevant information…” |

“It is important to engage in discussion actively…another important thing is to summarize the key points during the discussion. We reflected on classroom discourse by watching a video, and we could synthesize useful ideas from the discussions...” |

4.2 Students’ engagement in the analytics-supported classroom work

The second research question examined how students engaged in collective reflections and meta-talk supported by video-based learning analytics in developing their understanding of discourse. Students were provided with scaffolds working in groups on CDA (e.g., meaning of visualizations) and the teacher engages students in meta-talk on how they reflected on classroom discourse.

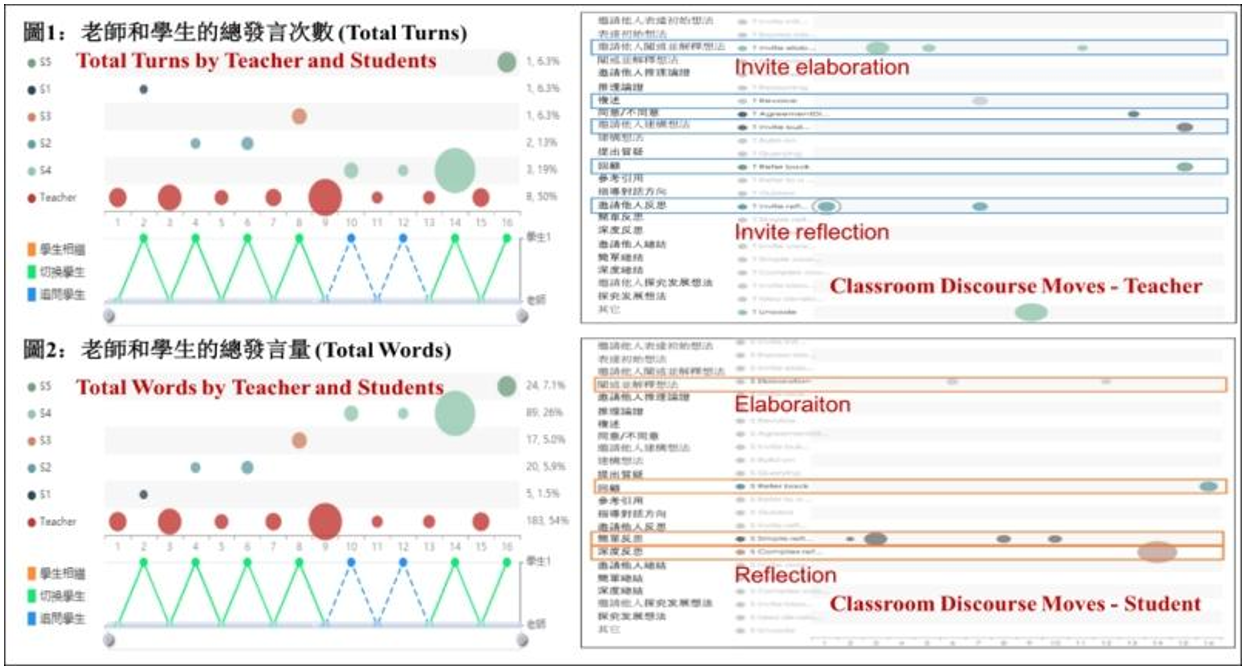

4.2.1 Developing awareness of progressive dialogue and community contribution through classroom meta-talk and CDA

Students watched video recordings of classroom discussions and discussed on CDA-generated visualizations. The excerpt on classroom meta-talk (Table 5, Teacher: “What did you notice about the classroom discussion?”) shows how students noticed several characteristics of the progressive nature of classroom discourse. The video clip and classroom meta-talk helped students to understand more about classroom conversations, not just as question-answer and agreement, but one that involved agency and inquiry from students collectively (e.g., “Different questions are asked”). The teacher also presented the CDA-generated visualization results to students, followed by a classroom discussion. S5 and S4 noticed the bubble size (e.g., “…they spoke a lot more than the teacher” and “… few students express their ideas”). This demonstrates that discussing the visualization results helps students notice the frequency of teacher and student participation in the classroom discussion. Primarily, these findings suggest that reflecting on classroom discourse by CDA and meta-talk helped students identify some components of productive discourse, such as distributed engagement, providing various ideas, and asking more questions to deepen the inquiry.

Table 5. An excerpt of classroom discussion illustrating students’ emergent understanding of knowledge building classroom discourse supported by a discussion on CDA visualizations.

|

Agent |

Classroom Discourse |

|

T |

What did you notice about the classroom discussion? |

|

S1 |

One question followed by one answer. |

|

S2 |

Different questions are asked. |

|

S3 |

Students asked some questions to continue their community inquiry. |

|

T |

Any other ideas? |

|

S4 |

They discussed a question and different students provided various ideas. Later on, they continued to ask questions based on the discussion…all the questions and ideas were connected. |

|

T |

Any other ideas? |

|

S5 |

Examples were provided to illustrate ideas. |

|

T |

Who provided the examples? The teacher or the students? |

|

S5 |

Students. |

|

|

The teacher showed students CDA-generated visualizations and explained the meaning of the bubble size in the graph |

|

T |

What did you get from this graph? |

|

S5 |

Students engaged in discussion a lot. They spoke a lot more than the teacher. |

|

T |

How about another graph? |

|

S4 |

The teacher spoke a lot, and few students expressed their ideas. |

4.2.2 Developing awareness of improving ideas through collective reflection using the CDA

Awareness of improving ideas plays an essential role in the knowledge building community, not only for expressing and sharing ideas through discussion, but also for improving and revising ideas through inquiry. Each group engaged in collaborative work to generate criteria for good discourse by comparing two classroom discussions. Students watched CDA video excerpts and discussed visualizations including classroom talk content, frequency of participation, and coding of productive discourse moves (e.g., “invite elaboration”, “elaboration”, “invite build-on”, “build-on”) (see Figure 3).

The following excerpt comes from an observation note taken by the researcher when observing Group 8’s work. It indicates that the students analyzed the CDA-generated visualization data and identified the lack of “build-on” and “querying” in the discussion.

“I see some ‘invite elaboration’ and ‘invite reflection’ by the teacher. I also see some ‘elaboration’ and ‘reflection’ by students. But I did not see any ‘build-on’ and ‘querying’ in this discussion. I am wondering whether we can have a good discourse if we do not build-on others’ ideas.” (Group 8, from observation notes when Group 8 worked on the CDA prompt sheet)

Figure 3. CDA-generated visualization results.

4.3 Discourse understanding model for knowledge building

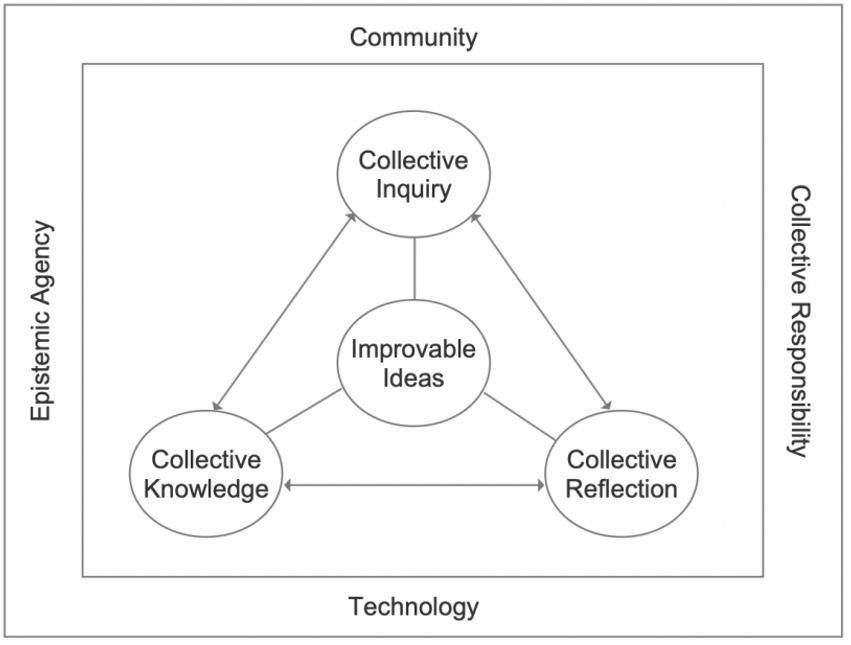

Taken different findings together, students shifted their epistemic understanding of discourse towards a knowledge building perspective. The classroom meta-talk using a video-based analytics-supported approach helped students to reflect on the nature of productive classroom discourse and develop an awareness of how to contribute to their community, which would have influenced their epistemic understanding of discourse.

This study identified three major changes in students’ epistemic understanding of discourse from the knowledge building perspective. By collective and continuing inquiry in class, students deepened their understanding of productive discourse in the process of improving ideas, developing collective knowledge, and synthesizing ideas with reflection. We also found that how students engaged in the meta-talk and collective reflection influenced their understanding of discourse. Figure 4 presents a model of understanding productive discourse toward knowledge building. It depicts three external influencing factors (collective inquiry, collective knowledge, and collective reflection) from the perspective of students’ epistemic discourse understanding process and one center influencing factor (improvable ideas) that sustains the working process. Working as a community, students take epistemic agency and collective responsibility for engaging in collective inquiry, collective reflection, and collective knowledge advancement with sustained idea improvement, supported by technology.

Figure 4. Discourse understanding model for knowledge building.

5. Conclusion and future directions

This study investigated students’ understanding and engagement in productive classroom discourse supported by a video-based analytics-supported approach in a knowledge building environment. Findings show that students’ epistemic understanding of discourse shifted from question-answer views toward progressive discourse. Facilitated by meta-talk and reflection on video-based visual analytics, students developed an emergent understanding of progressive knowledge building discourse emphasizing agency and community contribution. This study contributes to current literature on classroom discourse by expanding the nature of exploratory classroom talk to knowledge building discourse, and constructing a model of discourse understanding for knowledge building. It also highlights the promising roles of video-based analytics-supported approach in promoting understanding and engagement of productive discourse. Future research can examine the role of the designed approach in various contexts, and include more strategies (e.g., constructive uses of authoritative sources) for understanding knowledge building discourse. More influencing factors (e.g., rise above and technology use) can also be explored for the refinement of the understanding model.

References

Beisiegel, M., Mitchell, R., & Hill, H. C. (2018). The design of video-based professional development: A exploratory experiment intended to identify effective features. Journal of Teacher Education, 69(1), 69-89.

Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (2003). Learning to work creatively with knowledge. In E. De Corte, L., Verschaffel, N. Entwistle, & J. van Mer Merriënboer (Eds.), Powerful learning environments. Unraveling basic components and dimensions (pp. 55-68). Oxford, UK: Elsevier Science.

Borko, H., Jacobs, J., Eiteljorg, E., & Pittman, M. E. (2008). Video as a tool for fostering productive discussions in mathematics professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(2), 417-436.

Chen, B., & Hong, H.-Y. (2016). School as knowledge-building organizations: Thirty years of design research. Educational Psychologist, 51(2), 266-288.

Chen, G. (2020). A visual learning analytics (VLA) approach to video-based teacher professional development: Impact on teachers’ beliefs, self-efficacy, and classroom talk practice. Computers & Education, 144, 103670.

Chen, G. & Chan, C. K. K. (2022). Visualization- and analytics-supported video-based professional development for promoting mathematics classroom discourse. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 33, 100609.

Chen G., Clarke, S., & Resnick, L. (2015). Classroom Discourse Analyzer (CDA): A Discourse Analytic Tool for Teachers. Technology, Instruction, Cognition and Learning, 10(2), 85-105.

Greene, J. A., Sandoval, W. A., & Bråten, I. (2016). Handbook of epistemic cognition. New York, NY: Routledge.

Howe, C., & Abedin, M. (2013). Classroom dialogue: A systematic review across four decades of research. Cambridge Journal of Education, 43(3), 325-356.

Howe, C., Hennessy, S., Mercer, N., Vrikki, M., & Wheatley, L. (2019). Teacher-student dialogue during classroom teaching: Does it really impact on student outcomes? Journal of the Learning Sciences, 28(4-5), 462-512.

Major, L., & Watson, S. (2018). Using video to support in-service teacher professional development: The state of the filed, limitations and possibilities. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 27(1), 49-68.

Mehan, H. (1979). Learning lessons. Harvard University Press.

Mehan, H., & Cazden, C. (2015). The study of classroom discourse: Early history and current developments. In L. B. Resnick, C. Asterhan, & S. N. Clarke (Eds.), Socializing intelligence through academic talk and dialogue (pp. 13-36). American Educational Research Association.

Mercer, N., & Dawes, L. (2008). The value of exploratory talk. In N. Mercer, & S. Hodgkinson (Eds.), Exploring talk in school (pp. 55-71). London: Sage.

Mercer, N., Hennessy, S., & Warwick, P. (2019). Dialogue, thinking together and digital technology in the classroom: Some educational implications of a continuing line of inquiry. International Journal of Educational Research, 97, 187-199.

Paavola, S., Lipponen, L., & Hakkarainen, K. (2004). Models of innovative knowledge communities and three metaphors of learning. Review of Educational Research, 74(4), 557-576.

Scardamalia, M. (2002). Collective cognitive responsibility for the advancement of knowledge. In B. Smith (Ed.), Liberal education in a knowledge society (pp. 67–98). Chicago: Open Court.

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (2014). Knowledge building and knowledge creation: Theory, pedagogy, and technology. In R. K. Sawyer (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (2nd ed., pp. 397-417). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Seidel, T., Stürmera, K., Blomberg, G., Kobarg, M., & Schwindt, K. (2011). Teacher learning from analysis of videotaped classroom situations: Does it make a difference whether teachers observe their own teaching or that of others? Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(2), 259-267.

van Aalst, J. (2009). Distinguishing knowledge-sharing, knowledge-construction, and knowledge-creation discourses. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 4(3), 259-287.

van Aalst, J., & Chan, C. K. K. (2007). Student-directed assessment of knowledge building using electronic portfolios. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 16(2), 175-220.